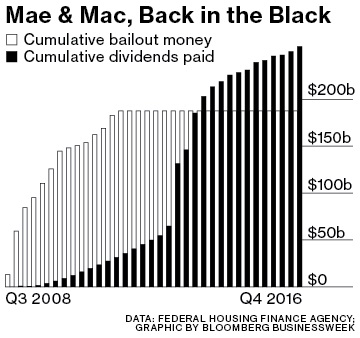

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were

among the biggest disasters of the financial crisis. In September

2008, nine days before Lehman Brothers failed, the federal government took over

the mortgage companies; it eventually spent more than $187 billion bailing them

out. The U.S. Treasury has received billions in profit that investors are suing

for.

For decades, the companies had

provided an implicit government backstop to the U.S. mortgage market, buying

loans from private lenders and guaranteeing payments to investors. That helped

spur a steady rise in homeownership—until the subprime crisis hit and Fannie

and Freddie were on the hook for billions in losses.

Lawmakers vowed to overhaul the

companies and some planned to wind them down completely. But more than eight

years later, Fannie and Freddie still operate under government control—and

they’re now a bigger part of the system, guaranteeing payment on just under

half of all U.S. mortgages, up from 38 percent before the crisis.

There is one key difference: Any

profits the companies generate go to the government instead of investors. The

latest payment, a combined $9.9 billion to the U.S. Treasury at the end of

March, pushed the total amount of cash Fannie and Freddie have paid to

taxpayers to $266 billion, making their bailout one of the most profitable in

history.

There’s now a pitched battle over

who should get those profits. The companies’ pre-crisis common and preferred

stocks still trade over-the-counter, and investors who snapped up the shares,

such as hedge fund managers Bill Ackman and John Paulson, say Treasury is

breaking the law by taking the money. The fight goes back to a change the

Barack Obama administration made to the bailout terms in 2012.

When the government took them

over, Fannie and Freddie issued Treasury a new class of preferred stock that

paid a 10 percent dividend, along with warrants to acquire almost 80 percent of

the companies’ common stock. In 2012 the government changed the terms to say

that every quarter Fannie and Freddie would send Treasury all their profits

except for a certain amount of money kept in reserve. That reserve started at

$3 billion in 2013 and was scheduled to fall by $600 million every subsequent

year, until hitting zero in 2018.

The department said this would

hasten the wind down of the companies. In 2013, Fannie and Freddie became

profitable again. All those earnings went to taxpayers, infuriating investors

who hoped to share in the rebound. Ackman, along with mutual fund manager Bruce

Berkowitz, and Richard Perry, a prominent hedge fund manager, said the changes

were illegal and sued. In more than 20 lawsuits, investors have made claims

including that the dividend payment is an illegal confiscation of private

property, that the government lied about its reasoning, and that the structure

of the regulator in charge of Fannie and Freddie, the Federal Housing Finance

Agency (FHFA), is unconstitutional.

Judges who’ve ruled so far have

come down on the government’s side. Matthew McGill, an attorney with Gibson,

Dunn & Crutcher who represents Perry in one of the cases, says Perry plans

to keep pressing his case. “This is a case where the government’s conduct and

the damage it’s done to investors is simply immense,” McGill says. An FHFA spokeswoman

declined to comment. Treasury didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Investors want the government to

begin the process of selling its stake in Fannie and Freddie by stopping the

dividend, but they don’t want the companies to go away. Ackman favors a plan

that would strengthen the companies and keep their activities largely intact.

“There is simply no credible alternative to Fannie and Freddie,” he wrote in a

letter to investors in March.

The Obama administration left it

to Congress to pass legislation dealing with the problem, but nothing has

emerged. Texas Republican Jeb Hensarling, chairman of the House Financial

Services Committee, wants to wind down Fannie and Freddie completely, while

some Democrats think they should be strengthened rather than killed.

Some small lenders and advocates

for affordable housing would also like to see the dividend suspended to let the

mortgage companies build their reserves. They’re nervous that any alternative

Congress might put in place would make it harder for lower-income borrowers to

get mortgages. Investors had hoped Donald Trump’s administration would move to

sell the government’s stake, but so far the view from the White House is

unclear. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has said that ending government control

is a priority, but that he’s focused on regulatory relief and tax reform.

In the middle of the debate is

Mel Watt, the Obama appointee who heads the FHFA and essentially controls

Fannie and Freddie. Watt has the authority to order the companies’ boards of

directors to suspend the dividend payments. He came close to doing so at the

end of March, just before Fannie and Freddie’s last payment was due, according

to people familiar with the matter. A group of senators wrote Watt a letter

that week, warning him against stopping payment, and Watt decided to make it.

Stopping the payment would have

let Fannie and Freddie build their reserves, making it less likely they would

need more money from taxpayers in the event of a loss. Under terms of the

bailout, the companies could still borrow up to $259 billion in an emergency,

so insolvency is a long way off. Watt, a former North Carolina congressman, has

told people around him that he’d consider it a dereliction of duty if the

companies needed more money on his watch.

Investors would’ve been thrilled

if Watt had withheld the dividend in March. Building capital is a necessary

precursor to selling Fannie and Freddie back to the private market, where their

shares could be worth billions. Mnuchin put one of his counselors, Craig

Phillips, in charge of the situation. In meetings, Phillips has floated ideas

as wide-ranging as putting the companies into receivership, which could wipe

out investors, as well as legislation to replace or supplement them with a new

system, according to people familiar with the matter. Clarity on what the

administration wants to do could be a long way off.

The bottom line: Fannie

Mae and Freddie Mac have paid $266 billion to the U.S. Treasury. Investors say

it’s time for them to get paid.

Click here for the original

article from Bloomberg.