Investors are pulling money out

of the U.S. stock market at one of the highest rates in years, moving billions

of dollars to other markets and scaling back a long-held bet that U.S. growth

would bring superior returns.

Global money managers’

allocations to U.S. stocks slumped to a nine-year low in April, according to a

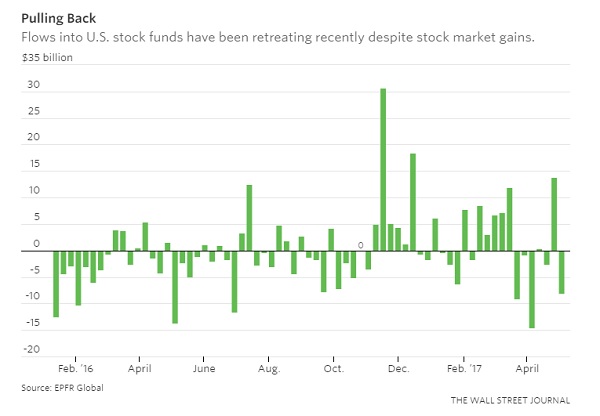

survey from Bank of America Merrill Lynch. And U.S. equity funds saw an outflow

of $22.2 billion during the six weeks that ended May 3, the largest six-week

redemption in more than a year, according to EPFR Global.

Much of the money is going to

Europe. Net inflows into European funds in the first three months of the year

hit a five-year high for the first quarter, according to Thomson Reuters

Lipper.

Emerging markets are also

benefiting. Strong manufacturing, industrial production and trade data in the

developing world helped attract the strongest three-month stretch of net

inflows to emerging-market funds since 2014, according to the Institute for

International Finance.

“The tables are beginning to

turn,” said Brian Singer, head of the dynamic strategies allocation team at

William Blair & Co., who has added to equity positions in places like

Spain, Italy, India and Russia. “The interest of investors, the conventional

wisdom and now the capital flows are starting to shift.”

Strong employment numbers on

Friday offered hope that U.S. economic growth might be accelerating after a

soft patch. Some global investors view the jobs numbers as a bullish sign for

U.S. stocks, especially if European growth shows any indication of faltering

after tentative signs of recovery. Even many investors lightening up on U.S.

stocks still have them as a core holding and don’t expect a mass exodus.

But if this shift in sentiment

continues, it would represent a significant change in course for global

investors. During most of the post-financial-crisis period, money managers have

tended to favor the U.S. as one of the few spots in the developed world

offering economic growth.

That status has helped propel

U.S. stock indexes to record highs, roundly beating most foreign markets in

recent years. From the start of 2009, the S&P 500 index has returned 166%

as the economy pulled out of the financial crisis. European stocks were up 99%

over that period, while volatile emerging markets returned 74%, according to

FactSet.

Now, some analysts say U.S.

stocks now look overvalued compared with the rest of the world. The cyclically

adjusted price-to-earnings ratio, known as CAPE, is 22 times in the U.S.,

compared with 16.7 in Europe and 13.7 in emerging markets, according to Makena

Capital Management.

Another reason for the shift:

Investors are betting that growth may be finally returning to Europe after

nearly a decade of fits and starts. The 19 countries in the European Monetary

Union grew by 0.5% in the first quarter, which equated to an annualized growth

rate of 1.8%. By comparison, U.S. output grew at an annual rate of 0.7% in the

first quarter.

Over the past five years, the

U.S. economy outgrew the euro area by 1.4 percentage points a year on average,

according to the International Monetary Fund. The IMF expects that gap to

narrow to 0.6 percentage point in the next three years.

The IMF has also been more upbeat

about growth in emerging markets. Many of these economies benefit from higher

commodity prices and a healthier global economy. Government stimulus appears to

have steadied growth in China, while the economies of Brazil and Russia are

expanding after two years of contractions.

The U.S. economic picture has

been mixed. Nonfarm payrolls rose by a seasonally adjusted 211,000 in April,

and unemployment fell. But closely watched indicators like auto sales and

consumer spending have fallen short of market expectations. Many

investors worry whether the U.S. economy is strong enough to justify lofty

stock valuations.

“There are a lot of mixed

signals” in the U.S., said Lance Humphrey, a global multiasset portfolio

manager at USAA. He recently reduced positions in U.S. stocks and added to his

holdings of Asian and Middle Eastern companies.

The political risk that has

hounded European markets for years may also be subsiding. The Greek debt

crisis, which started in late 2009, raised fears that the country could leave

the European Monetary Union. More recently, Britain voted to leave the EU, and

investors had been worried about a far-right candidate in France until centrist

Emmanuel Macron won on Sunday.

Yet even before the second round

of the French elections, business and consumer sentiment in Europe had been

rising. IHS Markit ’s purchasing managers index reached a six-year

high in the first quarter, and the European Commission’s consumer-sentiment

survey is near its highest since 2007.

“Now, the things that were

keeping you from leaving the U.S. are less worrisome than they were before,” said

Michel Del Buono, chief strategist at Makena Capital Management, which manages

$18 billion in assets. For about a year, Makena has been gradually deploying

new assets into stocks in Europe and emerging markets.

While European corporate margins

are still hovering around recession lows at 5%, margins in the U.S. are already

near records at 8.8%, according to Makena. That suggests “much less potential”

for earnings to further grow in the U.S., Mr. Del Buono said.

Still, some investors think

European stocks are cheaper for systemic reasons that will likely persist

despite the more encouraging recent data.

While growth is strong in

economic powerhouses like Germany, other countries continue to struggle. A glut

of bad loans has crimped bank lending in Italy, for instance, while Greece

faces fresh austerity measures. Europe’s unemployment rate, though declining,

stood at 9.5% in April, compared with 4.4% in the U.S.

Europe’s rapidly aging population

tends to hold a greater part of its wealth in savings, hampering government

efforts to boost consumer prices and spending. Stricter labor laws make it

harder for companies to let employees go during bad times, so companies are

more reluctant to add jobs during good times.

“Risks surrounding the euro-area

growth outlook, while moving toward a more balanced configuration, are still

tilted to the downside,” European Central Bank President Mario Draghi said at

an April meeting.

Some investors said that their

move out of the U.S. was in part due to a softening dollar. “In our view, we’re

about to see a secular peak in the dollar, unless there’s a big rise in

protectionism,” said Luca Paolini, chief strategist at Switzerland’s Pictet

Asset Management, with $477 billion of assets under management.

A weakening dollar would help

emerging markets, where yields are also more attractive. Starting from the

beginning of this year, Pictet has been reducing its exposure to U.S.

high-yield bonds, while increasing allocations to emerging markets, he said.

Click

here for the original article from the Wall

Street Journal.