It used to be that almost all mutual funds invested their

capital only in securities of public companies. But that’s been changing—which

could be good news for some small businesses that have big plans.

Thirty-six percent of firms going public in 2016 received

mutual-fund financing before their IPO, according to a recent research

paper by Michelle Lowry and Sungjoung Kwon, both at LeBow College of

Business, Drexel University, and Yiming Qian at the University of Iowa.

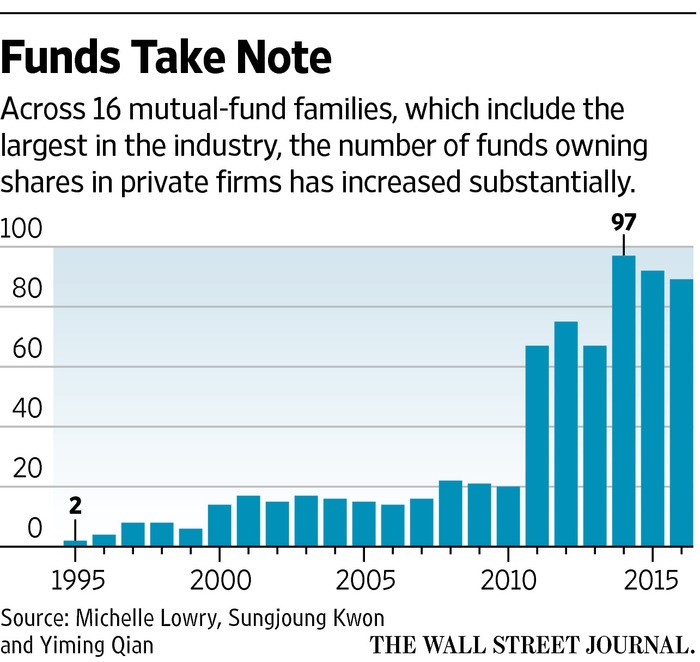

This practice of investing in private firms has become

increasingly widespread. Specifically, the authors say, fewer than 15 funds

invested in private companies each year through 2000, compared with around 90

unique funds in 2015 and 2016. The research used data from 16 fund families

from 1995 to 2016.

“The interest of mutual funds is driven by two things: the

possibly of investing in unicorns and the fact that these firms are going

public later and later,” says José-Miguel Gaspar, professor of finance at Essec

Business School in Paris. In other words, mutual funds want to get in early on

companies with potential for fast growth.

If this trend continues, it’s likely to be good for some,

but not all, small businesses. To get an investment from a mutual fund, a

company will need to offer something rather special. “I am not sure this is a

development for the average startup,” says Prof. Gaspar.

For instance, a small chain of pizzerias probably won’t get

too much interest from a mutual fund (other than when buying pizzas).

On top of that, the level of mutual-fund investment in

private firms, while growing fast, is still relatively small and likely to stay

that way. “Under the terms of a law from 1940, mutual funds are allowed to own

15% of their assets in private firms; guidance that came later suggested 10%,”

says Richard Evans, professor of finance at the University of Virginia’s Darden

School of Business in Charlottesville. “They can only put a small allocation in

such firms.”

But for those companies that can get a mutual fund

interested, there is plenty of good news.

Lower cost of capital. Prof.

Evans notes that the availability of more capital to fund businesses ultimately

means a lower cost of capital for the businesses. It goes back to economics

101—more supply lowers the price of the capital needed. In this case, the

potential returns that the investors want to see in the companies they buy will

be lower.

Stay private longer. “What

the paper shows is that having mutual-fund investors shows that companies can

stay private 1½ to 2½ years longer than otherwise,” says Prof. Lowry.

That allows the firms the potential to grow without the

pressure of reporting earnings each quarter. That means that profits can be

reinvested into the business and so help boost longer-term growth.

Less regulatory filing. Public

companies must file many documents each year. Staying private allows managers

to concentrate on growing the business rather than filling in government forms.

The longer they stay private, the longer they can avoid the paperwork.

Help with growing pains. Any

small company that wants to grow will see growing pains, but with a mutual-fund

investor, there are seasoned managers available to offer advice.

IPO prep. The advice isn’t just there

when there is a misstep. Perhaps most important, the advice and coaching can

help companies with their debut on the stock market, aka the IPO.

“The transition [from private to public] can be quite a big

change,” says Sonu Kalra, portfolio manager of the Fidelity Blue Chip Growth

Fund. He adds, “The leaders are used to sitting in a room with a few people,

whereas when they are public, it will be with a big group of people.”

Mr. Kalra says he and his team try to prepare company

managers for what to expect when their stock is listed. They hold mock earnings

conference calls, and mock roadshows where company leaders will talk with

investors.

Longer-term capital. Venture-capital investors are typically

involved for only a small part of a company’s life cycle. “As soon as the

company goes public the VC exits,” meaning they sell their stake, says Mr.

Kalra. “Whereas when the company goes public we’ll probably invest more

capital.” In other words, the relationship continues beyond the IPO.

Click here for the original article from

Wall Street Journal.