Tie together an algorithm, an

exchange-traded fund and an academic study finding an anomaly in the markets,

and voilà! You have a formula for making money. Trouble is, it turns out that

most of the supposed anomalies academics have identified don’t exist, or are

too small to matter.

A new study making waves in

quantitative finance tested 447 anomalies identified by academics and found

more than eight out of 10 vanish when rigorous tests are applied. Among those

failing to reach statistical significance: one anomaly recently set out by the

godfathers of quantitative finance, Nobel-winning economist Eugene Fama and his

colleague Kenneth French.

The study, “Replicating

Anomalies,” published this week by Kewei Hou and Lu Zhang at Ohio

State University and Chen Xue at the University of Cincinnati, is the biggest

test of examples of inefficient markets carried out so far. The trio applied

consistent analysis to the supposed anomalies, used the same database of stocks

and set higher standards for statistical significance. Simply reducing the influence

of the plethora of rarely traded penny stocks—which make up just 3% of market

value but 60% of all listings—by using market capitalization weightings made

more than half of past findings no longer significant.

Messrs. Hou, Xue and Zhang warn

that academics have been fiddling the statistics to come up with interesting

findings, known to statisticians as data mining or p-hacking. “The anomalies

literature is infested with widespread p-hacking,” they write.

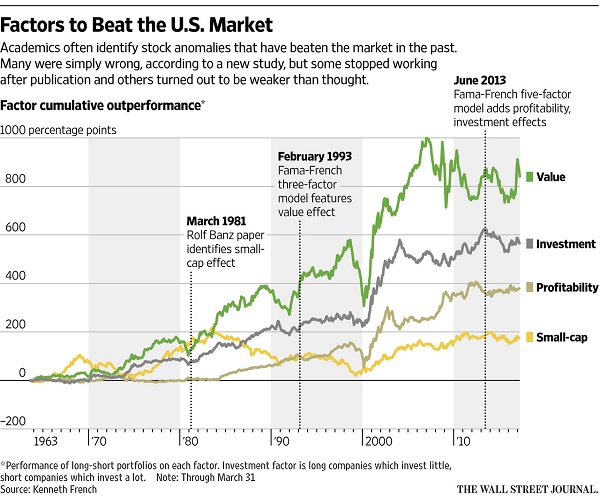

It isn’t all bad news for

investors and those trying to make a living flogging what have become known as

“factors.” The research confirmed that the most popular factors have indeed

outperformed the market over long periods even when faced with rigorous tests,

but found much smaller returns than previous studies estimated.

Market anomalies that passed the

new study’s tests included several of the biggest. Cheap stocks indeed beat

expensive ones; share prices have momentum; companies that invest a lot

underperform, and quality of earnings matters. Known as value, momentum,

investment and quality, these have become the biggest of the so-called “smart

beta” ETFs sucking in tens of billions of dollars.

A lot depends on exactly how the

factors are implemented, though, and the researchers dismissed one of the

industry-standard Fama-French factors as statistically insignificant: Companies

with high operating return on equity don’t outperform meaningfully on their

tests. Other measures of return on equity did outperform sufficiently, however,

underlining the sensitivity of some factors to exactly how they are defined.

One lesson for investors is to be

careful about trying to make money by repeating what seems to have worked in the

past. If it was so easy, everyone would do it and it would stop working.

A former student of Mr. Fama,

Cliff Asness, founder of quantitative hedge-fund manager AQR Capital

Management, said he tries to avoid being caught out by false findings by

trading on anomalies he can explain, economically or through investor behavior.

To assess whether the market anomalies will continue, he looks for ones which

carried on after being identified, can be seen in other markets or asset

classes, and where minor changes to how they are defined don’t much affect the

result. These include most famously value, momentum and corporate quality,

among others.

Still, he worries that the

“awesome effort” in the new paper might lead some to overreact and reject all

factors, even those which Messrs. Hou, Xue and Zhang found evidence for.

“Many factors are demonstrably

silly, or are highly correlated versions of the same idea,” he said. “Where I

get worried is about overreaction [to the paper] and the cynicism it breeds.”

Investors are still likely to be

confused. There are well over 100 value and high-dividend ETFs in the U.S.

alone, tracking large, small or midsize stocks, based on different definitions

and often combined with other factors such as momentum, quality or low

volatility. Intelligently choosing between them would mean examining how

indexes are constructed and comparing to the long-term academic studies to see

which methodology was best; in practice for most investors there is little more

to go on than a few years of performance data and fees.

Worse still, the markets are

reasonably efficient. If it turns out that shares usually rise just after

Christmas or fall on Mondays when it rains in New York, traders will quickly

find a way to profit from the anomaly, and it will disappear.

The danger for investors who have

piled into “smart beta” ETFs betting on value or quality is that exactly this

happens. Small-capitalization companies stopped outperforming after the

landmark study identifying the so-called small-cap effect in 1981, for example,

and haven’t looked good since (see chart).

Any factor that might keep

working after discovery has to be hard to arbitrage away. For quality, a story

can be told of get-rich-quick investors overpaying for sexy high-growth

companies, but not—until recently—for shares of boring providers of steady

profits. Whatever the story, the more popular the factor becomes with

investors, the smaller its outperformance will be in future.

Messrs. Hou, Xue and Zhang

provide a handy dismissal of factors which didn’t even work that well in the

past. But ultimately no one knows whether even previously robust factors like

value and momentum will keep working.

Click

here for the original article from Wall

Street Journal.